The battle for Spain

The Spanish Civil War was many things. It was a class war; a revolutionary and counter-revolutionary war; an antifascist and fascist war; a war fought in the name of both democracy and anti-communism. It was also a culture war in which the meaning of ‘Spain’ was at stake.

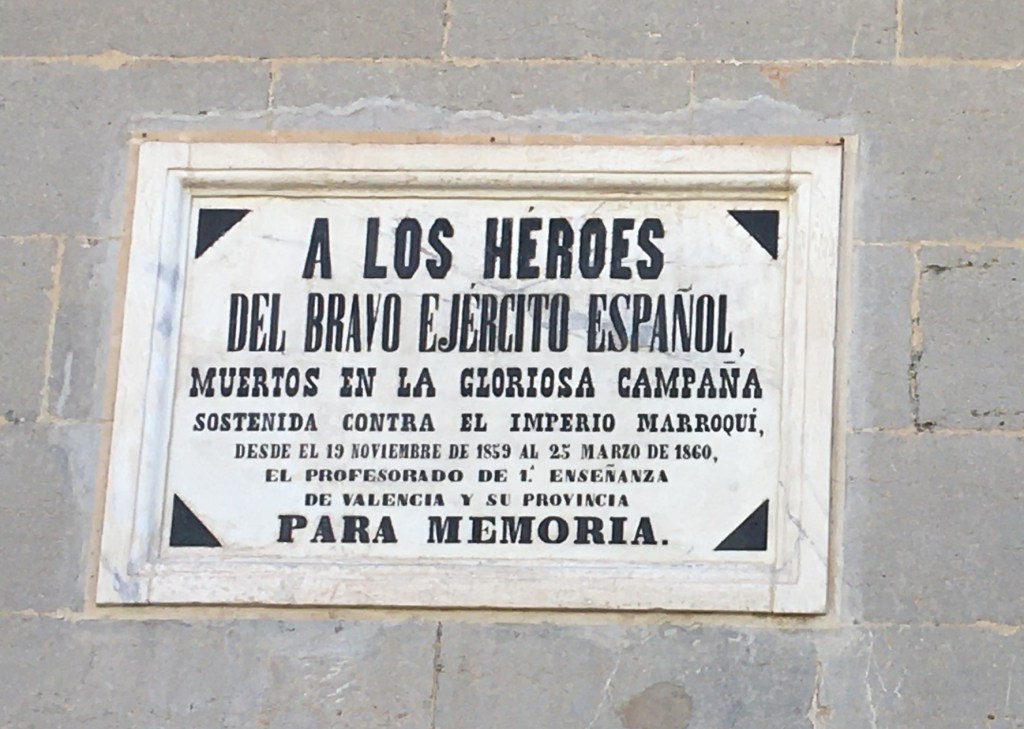

Traditionally, being Spanish meant empire, monarchy and Catholicism. The empire had been created by the monarchy to bring Christian civilisation to the world. But Spain lost most of her Latin American colonies in the early 19th century. Cuba, her one remaining jewel, was taken by the United States in 1898 at the peak of European imperialism. Attempts to forge an empire in Africa only reinforced a perception of weakness and decline. The War of 1859-60 with the Sultanate of Morocco, in which Spain occupied Tetuan for several months, sparked a patriotic response; the memorial plaque to the campaign’s ‘heroic’ soldiers in Valencia’s Plaza de Tetuán – referred to by Maria – is one of the consequences of this outburst of nationalism. However, the British would not allow extensive Spanish expansion in the region, and the creation of a Spanish enclave in northern Morocco in the early twentieth century was the product of broader colonial agreements between the traditional rivals of Britain and France.

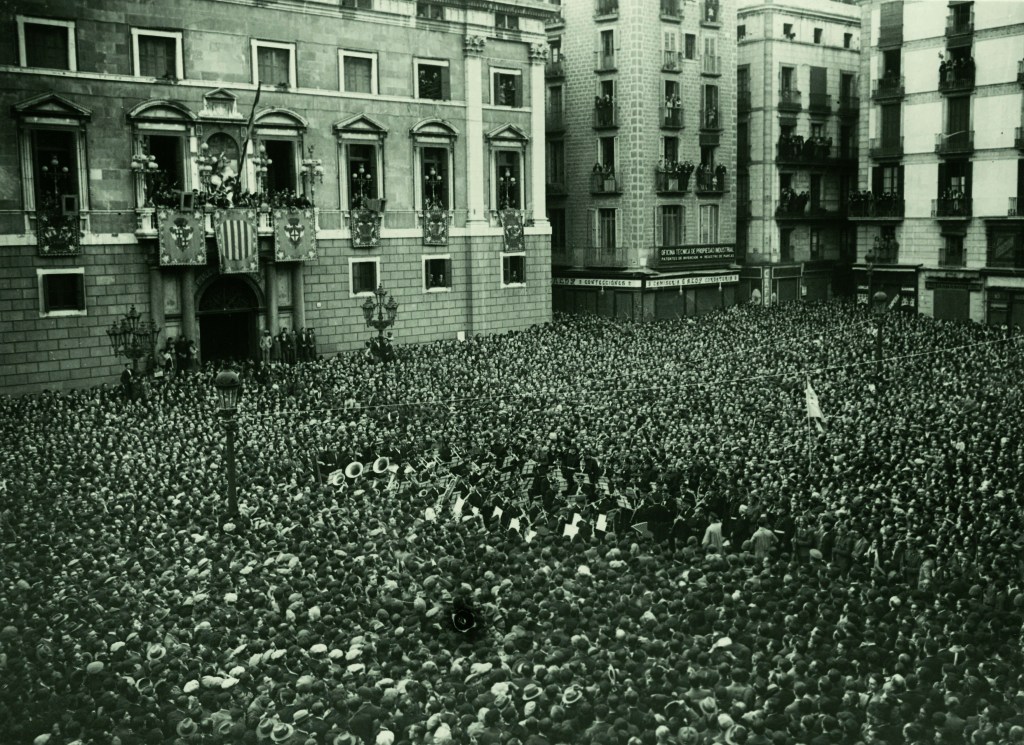

If Spain was no longer a powerful empire, it was no longer a monarchy in April 1931. Republicanism had been a minority creed in the nineteenth century, and the chaotic collapse of the short-lived First Republic (1873-74) did not enhance its reputation. Yet the disastrous loss of empire in 1898 contributed to a revival of the Republican movement, and it was particularly strong in the growing city of Valencia. Nevertheless, it was only after King Alfonso XIII decided to support General Primo de Rivera’s military coup that overthrew the liberal constitutional system in September 1923 that the monarchy was seriously imperilled. The King had tied the existence of the monarchy to a dictatorship, and when the dictator fled Spain in January 1930, he was fatally compromised, and he left the country in April 1931 when Spain’s towns and cities voted Republican in municipal elections.

Being Republican meant more than simply advocating for an elected head of state. Republican leaders like Manuel Azaña, the Civil War President, wanted to create a modern secular society. The Catholic Church, they argued, was one of the causes of Spanish decline. The December 1931 Constitution not only separated Church and State but banned religious orders from teaching. Many Catholics were horrified. They did not accept Azaña’s claim that ‘Spain has ceased to be Catholic’. They feared similar levels of persecution to that witnessed in Mexico after 1910 and especially Russia after 1917. These foreign examples remind us that church-state struggles were not confined to Spain. Indeed, France, Italy and Germany witnessed bitter anticlerical conflict from the mid-nineteenth century.

While the Church as an institution was not involved in the military rebellion of July 1936, many Catholics supported it on the basis that it would destroy what they regarded as communist inspired secularism. Although the rebels were successful in Spanish Morocco (including Tetuan) and large parts of rural Spain, they failed in the major cities with the important exception of Seville. The sense that the war was a crusade only deepened by the murderous anticlericalism of 1936. Just like in the French Revolution, women were at the forefront in the defence of the Church; they would be a central element of the clandestine Fifth Column that emerged throughout Republican Spain, especially in the cities of Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia. By definition establishing figures of fifth columnists is difficult, although it is unlikely that more than 7,000 belonged to its numerous networks. Nevertheless, many more would cooperate in their objective of weakening the Republican war effort.

Julius Ruiz

Further reading

- José Alvarez Junco, Spanish Identity in the Age of Nations (Manchester University Press, 2011)

- Nigel Townson (ed.), Is Spain Different? A Comparative Look at the 19th & 20th Centuries (Sussex Academic Press, 2015)

- Stanley G. Payne, The Spanish Civil War (Cambridge University Press, 2012)