Artisans and literacy

Artisans frequently crossed the bridge over the river Loire to trade or to visit the city’s markets. In the fifteenth century a remarkable number of artisans were involved in the city’s defense, guarding the walls, the gates and the bridge. Despite their social and economic status, these men and women increasingly participated in cultural life and intellectual debate.

It is a common assumption today that medieval artisans were not able to read and write and that during the Middle Ages literacy would have been particularly low. This seems to be confirmed by assessments of literacy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, showing that in France 33.3% of men and 12.5% of women were able to sign their marriage contracts.

However, recent research has shown that literacy does not always progress smoothly, and that reading and writing were much more common in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries than in later periods, notably in cities. Jehane Bernarde, the inspiration for the guide in the Hidden Tours app, owned ten books when she died in 1516 and there are many reasons to assume that she could read and write. Like other artisans, Jehane and her husband kept a record of their sales and debts in a personal account book.

Starting from the mid-twelfth century, schools for the urban population are documented in the northern half of present-day France. Young children started with primary education for one or more years, which included learning the alphabet, and reading prayers such as Our Father and Hail Mary. The Middle French vernacular was often used as a stepping stone to Latin, including reading the Latin Book of Hours and learning Latin grammar. Arithmetic and bookkeeping could also be part of the teaching program. Documentation from Valenciennes, Paris, and Tours survives that shows female teachers were also active in primary education. Pupils usually had to pay for tuition, but most schools had a small number of free places for poor children. Thus, literacy reached even the lowest social level of urban societies.

Late medieval books sometimes contain traces of reading and writing left by readers from a distant past. French Books of Hours often had blank spaces so that readers could add extra texts themselves. There is also evidence showing that people, including artisans, occasionally copied their own books.

Part of the population did remain illiterate. However, this does not imply that illiterate people were excluded from textual cultures. Religious texts in Europe’s vernaculars abound in exhortations stating that illiteracy is not an excuse to remain ignorant and that people should find someone to read aloud for them. Similarly, literate people were advised to share their books and their knowledge with household members, relatives, and neighbours.

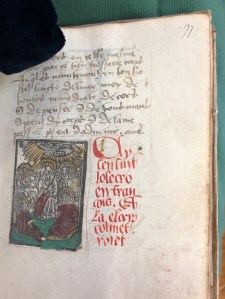

A home-made book of hours

In red ink, Colinet Rolet noted that he copied this Book of Hours himself. The pasted-in engraving represents the outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and Mary. Not every book in the late Middle Ages was made by a professional copyist. Medieval readers sometimes copied texts for their own use. In many cases this was out of necessity, in order to have a cheap copy. But hand copying religious texts was also perceived as a spiritual exercise assisted by the Holy Spirit.

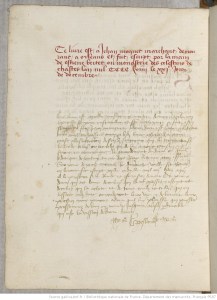

Written by a stocking maker

A trace of artisan literacy and writing skills can be found in this manuscript with the Life of Christ in French. In 1467 a stocking maker from Orléans (also in the Loire valley, 100 km east of Tours) named Guillaume Meslant wrote on the last page an ex-libris note asking those who borrowed the book from him to return it and to use it to improve their lives. It is the text in light brown ink beneath the inscription in red.

Margriet Hoogvliet

Further reading:

Paul Bertrand, Les écritures ordinaires. Sociologie d’un temps de révolution documentaire (entre royaume de France et Empire, 1250-1350), Paris, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2015; online edition https://books.openedition.org/psorbonne/29449.

Alain Derville, “Alphabétisation du peuple à la fin du Moyen Age”, Revue du Nord 66 (1984) 761–76.

Sabrina Corbellini and Margriet Hoogvliet, “Writing as a religious lieu de savoir”, le Foucaldien 7 (1):4, DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/lefou.92

Julie Claustre, Faire ses comptes au Moyen Âge : les mémoires de besogne de Colin de Lormoye, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2021.