Water from the well

‘Venice is in the water, but has no water’, as the Renaissance diarist Marin Sanudo put it – that of course because it is a saltwater lagoon and as such no fresh water is readily available for human consumption. Fresh water was an extremely precious commodity, and as the city grew to a population of around 150,000 by 1500, so the demand kept going up.

Modern-day visitors to the city will notice well-heads on almost every square and even on some streets as well as in the small courtyards of private houses. Surfaces were carefully paved with stone to ensure all rainwater would funnel water to gutters that captured rainwater. Below these paved surfaces was a stone or brick-lined cistern, partially filled with sand to filter the water of impurities, while drawing the clean water to a central well-shaft. Various specialist trades facilitated this essential amenity, keeping the cistern and campo clean, controlling access, and increasingly supplementing rainwater by transporting fresh water from the Brenta river on the mainland at Lizza Fusina to fill the wells manually. Large, flat bottomed barges (burci) conveyed the water from the mainland and was delivered by water carriers (acquaroli) directly to the network of cisterns.

As so often in the pre-modern period, all this complex infrastructure was given visual expression in the elaborate well heads (vere da pozzo) beautifully sculpted from luxury material, usually the pristine white stone from Istria, or the pink marble from near Verona. Quite often their shape was derived from column capital designs, and some may even have been repurposed capitals, though by the early sixteenth century the form used at San Vio had become quite popular. Here, a near-cylindrical octagonal design displays low relief sculptures of parish name saints separated by attractive swags; ironwork features would have included a pump spout on one side and a lockable lid to control access. Sometimes, if a local worthy had subsidised the cistern, they would be commemorated by an inscription.

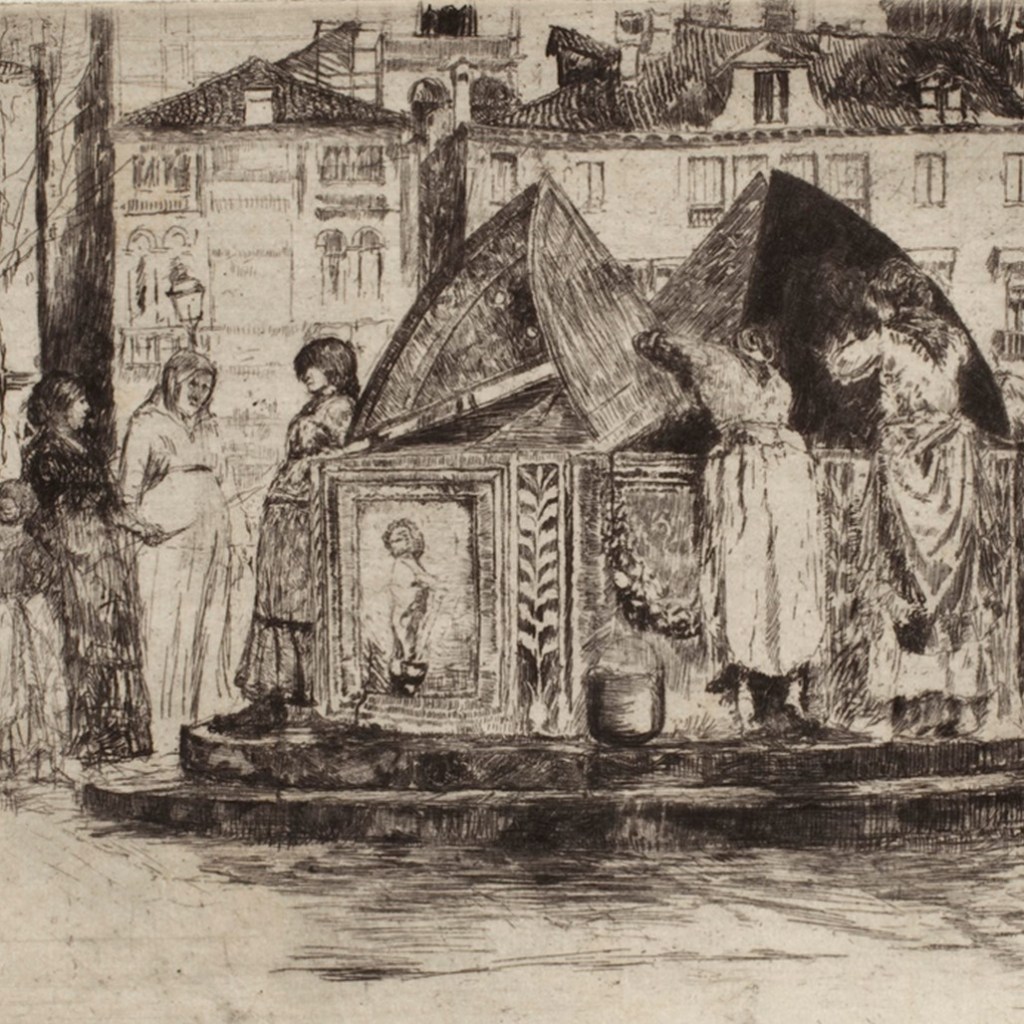

A number of city officials were charged with ensuring that water remained clean and uncontaminated, and local resident groups managed the twice-daily opening of the well. As locals gathered to collect water to bring home, these sites served as key nodes of community sociability. As the nineteenth- century print (pictured) reveals – access to water for these residents would have been largely unchanged for four hundred years.

Fabrizio Nevola

Further reading

David Gentilcore, ‘The cistern-system of early modern Venice: technology, politics and culture in a hydraulic society’, Water History (2021) 13: 375–406

‘Well Head, 1490-1500’, V&A online catalogue (consulted 18 October 2023): https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O117735/well-head-well-head-unknown/

A. Rizzi, Vere da pozzo di Venezia: i puteali pubblici di Venezia e della sua laguna, Venezia: Stamperia di Venezia, 1992