The laity and the cathedral

Medieval churches and cathedrals, such as Saint-Gatien’s, were spaces where the material presence of the sacred could be experienced. The choir and the main altar were usually cut off from the rest of the church by a rood screen. This space was most of the time reserved for the clergy, but lay boys who sang in the choir also had access.

Lay involvement in churches and cathedrals was an important aspect of medieval religion. Men, women and children did not only enter in order to attend mass, but for a number of other activities. The book of donors to Saint Gatien’s cathedral not only mentions donations by clerics, but also by lay people from all walks of life, including locals of Tours such as Petronilla Labure who donated her house in front of the cathedral in exchange for commemorative prayers by the canons.

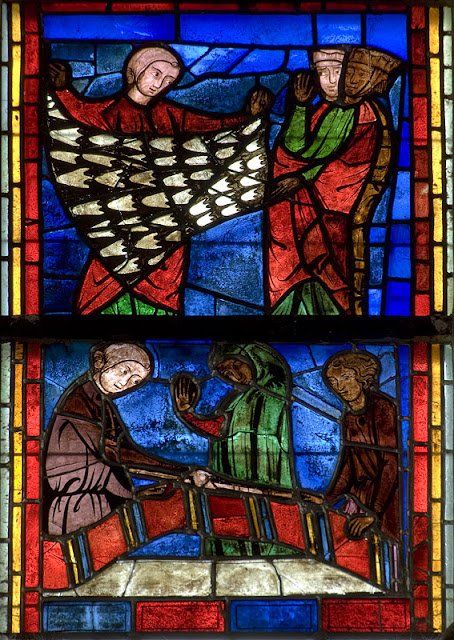

Lay people are also visible in the thirteenth-century stained-glass windows surrounding the choir. In one of them the lay donors Mathene and his wife Dionisia are visible together with their occupation, selling woollen cloth and fur.

Churches were also used for the religious education of the laity. An inventory made in 1539 of the objects in Saint Gatien’s cathedral owned by the lay church stewards includes a series of seven tapestries representing the story of Christ’s Passion from Palm Sunday to the descent of the Holy Spirit. The same inventory mentions another set of sixteen much older tapestries, also representing Christ’s Passion. The inventory makes clear that these tapestries were on display around the choir, so that lay people walking in the church could see the story of Christ’s Passion and read the biblical texts accompanying the images.

Lay people from Tours could also use the cathedral’s library to read about religious topics. The collection included texts in French, and a few surviving books contain notes about the obligation to return the books after use to the cathedral. Finally, many lay inhabitants of Tours were member of the confraternity attached to the cathedral. The membership list was unfortunately lost in the fire of 1940.

Stained glass windows

These thirteenth-century stained glass windows in the canon’s choir of the cathedral depict lay donors, Mathene and his wife Dionisia, together with objects representing their occupation, selling woolen cloth and fur.

Church tapestry

The tapestries from Saint Gatien’s cathedral do not survive. This tapestry is from a demolished parish church in Tours, Saint-Saturnin. It gives a good impression of what late medieval church tapestries looked like, with texts in French underneath the images. These tapestries were donated by Jacques de Beaune, owner of the hôtel de Beaune-Semblançay (formerly hôtel de Dunois) in 1527.

Margriet Hoogvliet

Further reading:

Sabrina Corbellini and Margriet Hoogvliet, “Late Medieval Urban Libraries as a Social Practice: Miscellanies, Common Profit Books, and Libraries (France, Italy, the Low Countries)”, Andreas Speer, Lars Reuke, eds., Die Bibliothek – The Library – La bibliothèque: Denkräume und Wissensordnung, Berlin, De Gruyter, 2020, pp. 379-398.

Thomas Rapin, Julien Noblet, “Le Cloître de la Psalette. Rappel chronologique (XVe, XVIe et XIXe siècles)”, Bulletin de la Société archéologique de Touraine 48 (2002), pp. 89-104.

Léopold Delisle, “Liste des manuscrits du fonds de Saint-Gatien”, Notice sur les manuscrits disparus de la Bibliothèque de Tours pendant la première moitié du XIXe siècle, Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1883, pp. 160-168.

Laura Weigert, Weaving Sacred Stories: French Choir Tapestries and the Performance of Clerical Identiy, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.