The book of nature

The University of Copenhagen in the 1600s had little in common with today’s University of Copenhagen, other than its name and location. Not only was the University much smaller, it was more or less just a vicar’s school. The Faculty of Theology was, therefore, the largest and most prominent of the four so-called classical faculties, which besides theology, included law, philosophy, and medicine. This had been the case since the University was inaugurated in 1479, but during the 17th century, it slowly began to change.

Today, most people think of religious and scientific worldviews as opposites. For example, was the universe created by God or by the Big Bang, and similarly, was man created by God or the result of a long evolutionary process? However, this is a modern distinction. For theologians, and most doctors and astronomers, of the 17th century, it was unthinkable to imagine a contradiction between science and theology. For them, it was beyond doubt that God had created the world and all the life it contains: human beings, animals, plants. Thus, studying the anatomy of animals and humans offered insights into the laws of nature that reflected the underlying divine order. People talked about the Book of God (the Bible) and the Book of Nature (scientific observations). Roughly speaking, there was no contradiction between biblical studies on the one hand, and anatomical dissections or astronomical observations on the other. Each of these studies furthered an understanding of how the world was connected.

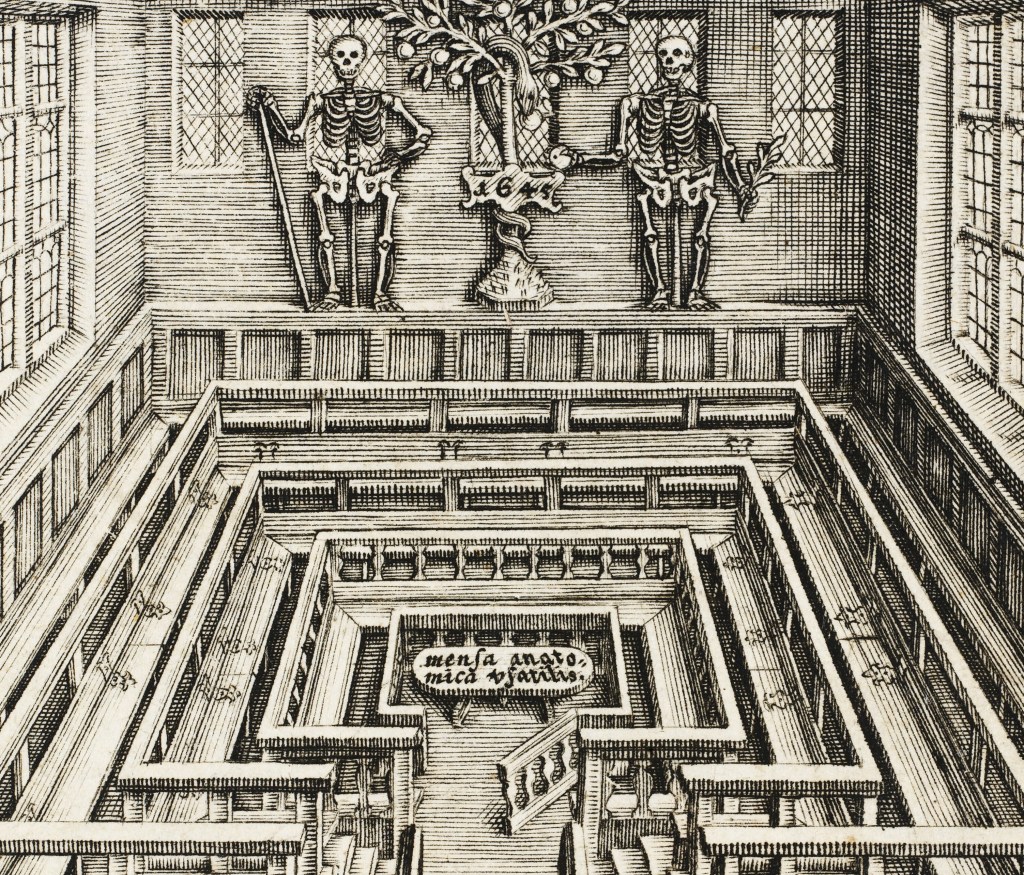

In 1644, the anatomical theatre, located where the main university building is today, was opened and specially equipped for dissections. It was still functioning in 1673, but it had been used less and less over the years, and the building went up in smoke during the Copenhagen fire of 1728. The physician Thomas Bartholin described the building in 1662, and it appears that the dissection hall was constructed as an amphitheater with a table in the middle and the spectators sitting on concentric rows of benches all around. On the wall behind the rows of seats were skeletons of animals and two people. The two people were called Adam and Eve, and a tree was placed between them. This reference to the biblical story of Adam and Eve can be seen as another expression of the close connection between the University, science, and the Church.

Physical proximity further underlines these close links. Copenhagen Cathedral was only a few meters from the University, and since the Reformation, the University had used the so-called Kapitelhus – a side building of the Church – for lectures and teaching.

The figure of the monarch also helped tie religion and science together. The Lutheran Church played an essential role in consolidating Denmark’s newly established absolutism. Indeed, much political theory of the period argued that the King had received his authority from God, so to oppose him was to oppose God. Theologians and priests, therefore, preached unconditional obedience to the King, the government, and the Church. At the same time, Christian V, like many absolutist monarchs, saw scientific endeavour as prestigious and believed that supporting science helped legitimise their rule.

Jesper Jakobsen

Further reading

Morten Fink-Jensen: Fornuften under troens lydighed. Naturfilosofi, medicin og teologi i Danmark 1536-1636, Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanums Forlag, 2004

Thomas Bartholin: Anatomihuset i København, Copenhagen: Loldrups Forlag, 2007