Anticlericalism and the fifth column

Violent anticlericalism has been a feature of modern Spanish history, particularly in periods of political instability. In July 1834, there was an outbreak of cholera in Madrid during the First Carlist War, a struggle between the Carlists, the absolutist supporters of Don Carlos for the Spanish throne, and the liberal regency of María Cristina. Convinced that monks had poisoned the water supply, a mob killed 73 priests and religious. In May 1931, a month after the proclamation of the Second Republic, a monarchist meeting in the Spanish capital infuriated leftists who attacked religious buildings. The violence soon spread throughout Spain and anticlericals burnt nearly 200 churches. The Franciscan church of San Lorenzo in Valencia, opposite the Borgia palace, was one of those that survived, even if the interior sustained damage.

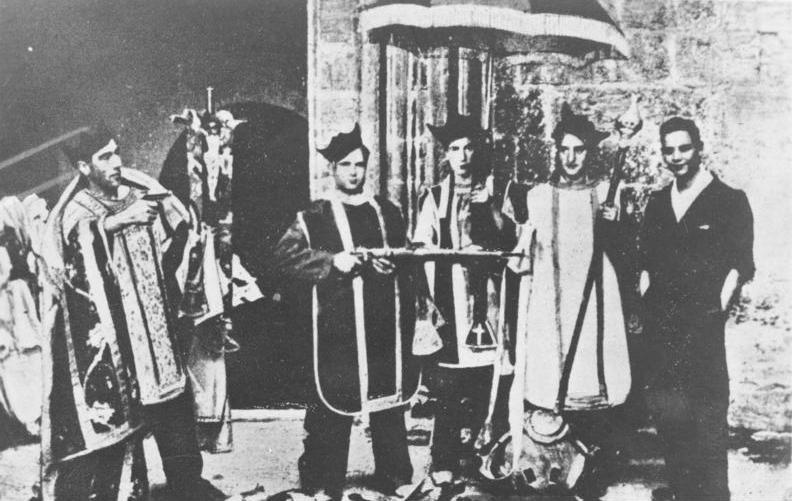

However, what was unique about popular anticlericalism in 1936 was its sheer scale. Although not directed by the government, the murders of priests and religious were accompanied by the mass sacking of churches, convents and monasteries; those buildings not destroyed were converted for secular use. The Catholic Church was to have no role in the new antifascist society.

Murderous anticlericalism seriously damaged the Republic’s international reputation and the Popular Front government of Largo Caballero largely brought the revolutionary violence to an end in the winter of 1936-37. Nevertheless, with the significant exception of the Basque Country, public Catholic worship could not take place as the Church continued to be seen as an integral part of the ‘fascist’ enemy. To some extent, this was a self-fulfilling prophecy, as Catholics (including surviving priests), became involved in the Fifth Column. In October 1936, the Communist newspaper Mundo Obrero reported that the rebel leader General Mola had declared that the four columns advancing towards Madrid would not take the capital; it would fall to a ‘fifth column’ inside it. Historians still debate whether Mola coined the expression, although it is true that a clandestine ‘fifth column’ capable of taking a city did not exist in Republican Spain in 1936. Ironically, it was the Nationalist failure to take Madrid in the winter of 1936-37 that made fifth columnist activity more likely, as Franco’s victory become more remote. Hitherto tiny and dispersed groups of rebel sympathisers came together, and consolidated secret networks were in increasingly regular contact with Francoist military intelligence. The latter were interested in military information, not a rising, and the Fifth Column was primarily concerned with intelligence gathering, providing spiritual and financial support to rightists, encouraging defeatist sentiments among their enemies, and preparing for a settling of accounts after the war.

If the Fifth Column emerged as a significant menace after it became evident that the conflict would not end in 1936, the Largo Caballero government reorganised the police to meet the threat. The revolutionary ‘checas’ gave way to dedicated squads dedicated to rooting out subversion. In Valencia, for example, a ‘special services’ team operated under the direct supervision of the Interior Minister, Ángel Galarza.

The reorganisation of the police was part of a more general process of the centralisation of power within the Republican state. The war was becoming bigger. In 1936, around 100,000 volunteered to fight for the antifascist militias; by March 1937, a new mainly conscript based Popular Army contained 300,000 troops. Equipping this force did not come cheap, and the Republicans used Spain’s gold reserves to purchase weapons, mainly from the Soviet Union due to the Western-sponsored policy of non-intervention. The policy of centralisation is closely linked to the Socialist Juan Negrín, who became Prime Minister in May 1937. He remains a controversial politician. For some historians, he was a Churchill-type figure who sustained Republican resistance against all the odds until 1939; for others, he was a counter-revolutionary allied to Stalinist communism.

Julius Ruiz

Further reading

- Julio de la Cueva, ‘Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War’ in Journal of Contemporary History, Vol.33 (3), p.355-369

- Julius Ruiz, The ‘Red Terror’ and the Spanish Civil War: Revolutionary Violence in Madrid (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

- Gabriel Jackson, Juan Negrin: Physiologist, Socialist, and Spanish Republican War Leader: Physiologist, Socialist, & Spanish Republican War Leader (Sussex Academic Press, 2010)