Bombing and Total War

Aeroplanes played a significant role in the military course of the civil war from the very beginning. In the first airlift in modern European history, Nazi transport planes carried part of Franco’s powerful but stranded colonial army from Morocco to Andalusia at the end of July 1936. Other colonial troops were shipped across the Strait of Gibraltar under Italian aerial protection. Hitler and Mussolini’s decision to intervene transformed Franco’s military and political prospects. By November, he was at the gates of Madrid as ‘generalissimo’, or undisputed rebel leader.

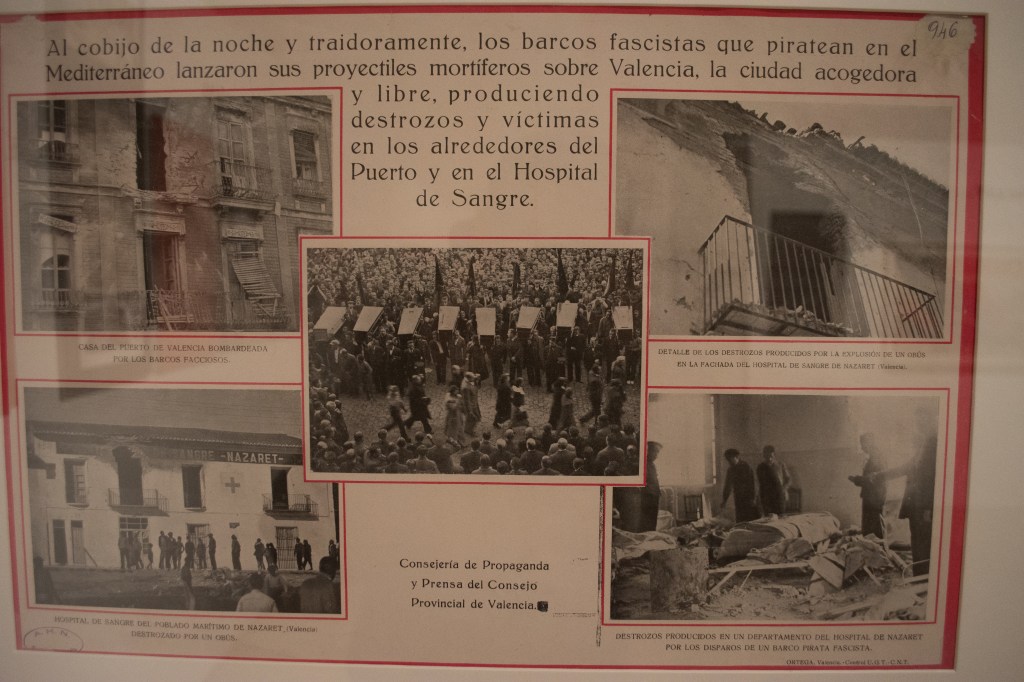

Francoist control of the skies was challenged by the arrival of Soviet aircraft in October. Stalin’s planes, in particular the I-16 fighter known by Republicans as the ‘Mosca’ (‘fly’), were as good as anything that Hitler and Mussolini could supply Franco, and antifascist Madrid survived. Yet the failed Nationalist offensive on Madrid in 1936 was an ominous portent of what was to come. Aerial bombardment, combined with artillery shelling, caused significant destruction and loss of life. The arrival of the German Condor Legion by the end of November greatly increased Francoist fire power, even if it could not turn the tide of battle in Madrid. Other Republican towns and cities became targets. In Valencia naval and aerial bombardment claimed at least 825 lives. More would have died if it had not been for the network of 250 air raid shelters.

Foreign observers were both captivated and alarmed by these events. In the 1920s, the Italian military theorist Giulio Douhet had claimed that mass terror bombing of cities could force an enemy to surrender without losing on the battlefield, and many Europeans believed that any future general war would begin by air raids. In his 1936 film Things to Come, the famous British novelist H.G. Wells conjured up a future world destroyed by bombers. This horrifying prediction gained credence with the Francoist offensive to conquer the Basque Country in the spring of 1937. German and Italian planes attacked the small town of Durango between 31 March and 4 April, killing 336 civilians. Wolfram von Richthofen, the Condor Legion chief of staff, had ordered his pilots to destroy military targets ‘without regard for the civilian population’. Similar instructions were given for the raids on Guernica on 26 April 1937, but unlike the destruction of Durango nearly four weeks earlier, foreign war correspondents such as George Steer of the London Times were at hand to report the bombing. Such was the devastation- nearly 74% of buildings were destroyed- that it is difficult to establish the number of deaths, but 300 is a minimum estimate, and the true figure is likely to be much higher.

The international outcry over Guernica prompted Franco to blame the victims themselves for the destruction, as well as prompting Pablo Picasso to choose the atrocity for his canvas that was displayed at the 1937 World Fair in Paris. Despite this, Francoist terror bombings of Republican towns and cities, particularly Barcelona and Valencia, continued to the end of the war.

Yet Spain did not substantiate Douhet’s thesis. An implicit recognition of this came in the winter of 1938-39 when Nationalist planes began to drop bread rather than bombs to a now starving Republican population. But the supposed efficacy of air power contributed to the capitulation of the Western democracies to Hitler at Munich in September 1938, as well as to the strategies of the belligerent powers in the Second World War. Guernica is now placed alongside Coventry, London, Hamburg and Dresden (among many others) as symbols of the horrors of total war.

Julius Ruiz

Further reading

- George Steer, The Tree of Gernika: A Field Study of Modern War (Faber & Faber, 2011)

- Michael Alpert, Franco and the Condor Legion: The Spanish Civil War in the Air (IB Tauris, 2018)

- Richard Overy, The Bombing War: Europe 1939-1945 (Penguin, 2014)