Propaganda machine

Propaganda played a crucial role in the consolidation of fascist power between 1922 and 1943. It was a process characterized by a considerable programmatic investment, aimed at using the mass media to influence public opinion and shape national identity according to fascist values.

The themes at the center of fascist propaganda changed in part with the evolution of the regime. The populist nationalism of the beginning was joined by other themes and “discourses”, such as the stability of the country, social cohesion, land reclamation, the battle for grain, the construction of new cities, industrial development, imperial conquests, and the civilizing mission of the Italians. The fundamental object of the regime’s propaganda was represented by its leader, Mussolini, whose image was celebrated in every form.

Fascist propaganda was exercised through control of the media. Having a long experience as a journalist and understanding of the great power of the press, Mussolini ensured that newspapers were under the strict surveillance of the regime. The militant fascist press was flanked by the bourgeois press, formally independent but in fact aligned with government policy. The Ministry of Popular Culture (MinCulPop) was established to censor and direct media content, ensuring that only information favorable to the regime was disseminated. The themes and topics covered by the press were in fact established and “suggested” by government apparatuses, which used press agencies to centralize and control news.

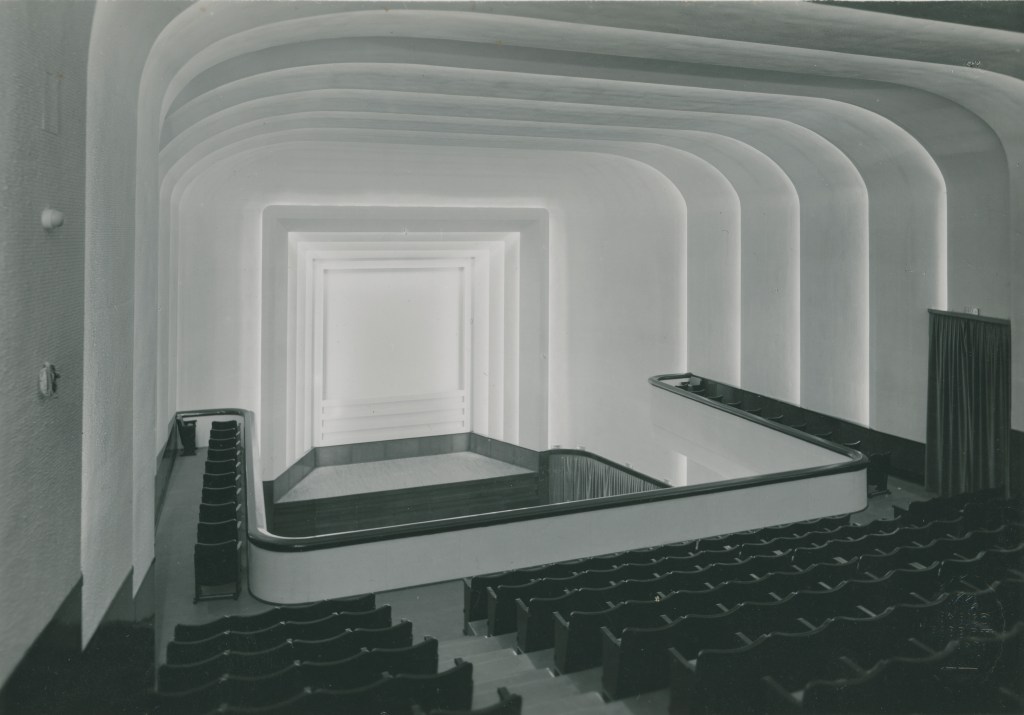

Cinema and radio were equally important tools of fascist propaganda. The Istituto Luce, founded in 1924 and nationalized in 1925, was used to produce and distribute news programs and films that glorified Mussolini and the regime’s achievements. Newsreels played an important role, a privileged instrument of official information, aimed at recounting the regime’s achievements in a rhetorical and triumphalistic tone and celebrating the image of the Duce.

In the cinematographic field, there was no shortage of explicitly propaganda films (Camicia nera, 1933; Lo squadrone bianco, 1936; Scipio l’africano, 1937), but entertainment films for the lower middle classs (so-called “white telephone” cinema) were preferred. The radio, which had become a mass medium in the 1930s, made it possible for Mussolini’s speeches to reach a vast audience, further strengthening the cult of his personality. School and cultural hubs were spaces of great importance for fascist propaganda. The regime intervened heavily in the educational system, modifying school programs to inculcate fascist values in young Italians. Textbooks were rewritten to exalt Italian history and culture, portraying fascism as the natural culmination of national greatness. Youth organizations, such as the Balilla for boys and the Piccole Italiane for girls, were created to indoctrinate new generations from an early age, promoting obedience, militarism and patriotism.

Maurizio Cau

Further reading:

S. Salustri, Orientare l’opinione pubblica. Mezzi di comunicazione e propaganda politica nell’Italia fascista, Unicopli, 2018

A. Gagliardi, “Educare” o intrattenere? Propaganda, mass media e cultura di massa, in G. Albanese (ed), Il fascismo italiano. Storia e interpretazioni, Roma, Carocci, 2021, pp. 255-279