Plague saints

City topographies are marked by the names of the collective sites of devotion that serve local communities, and it often seems you can’t turn a corner without running into another church.

In fact, the square to the side of this church (Campo San Sebastian) has another church backing onto it, dedicated to archangel Raphael. As you walk across the square a well head is prominently visible and on it an inscription in gothic capitals tells a story. Dated July 1349 it was erected by Marco Arian, in memory of his father Antonio. As the date makes clear – and a surviving will also confirms – Antonio died during the devastating plague of 1348 and left monies to provide a new well for the residents of the neighbourhood. As is well known, the so-called Black Death decimated urban populations, but stone records of this sort are quite rare, albeit that last testament bequests are responsible for huge amounts of charitable giving that led to the construction of churches and hospitals across Italy.

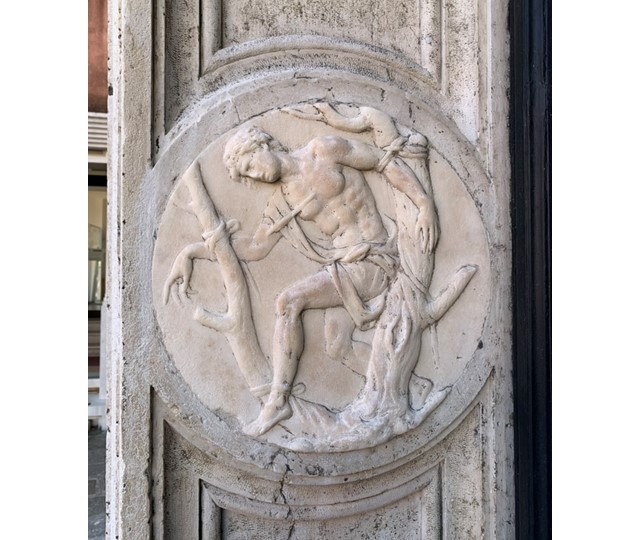

As a trading city connected constantly with both the mainland but especially to the principal sea routes of the Mediterranean and beyond, Venice was especially susceptible to plague and diseases that travelled alongside merchants and their goods. The city invented and developed a sophisticated system of quarantine, but on regular occasions plague ripped through the city, devastating the population. A number of churches serve as monumental markers of the effects of plague, commemorating the city’s survival through particularly violent outbreaks, but of course also honouring its victims. The route of this trail connects a number of them. Santa Maria dell Salute (on the Grand Canal), was built to mark the end of the plague of 1631, its massive stone mass supported on millions of wooden pylons driven into the ground as part of Baldassare Longhena’s ambitious plans. Across from the Zattere on the Giudecca, the pristine white temple front of Andrea Palladio’s church of the Redentore was built after the plague of 1576. San Sebastiano is instead invoked for a number of plagues, but owes a first stage of reconstruction to a wave of disease beginning in 1464, but continuing into the following century. A number of the sculptures and reliefs on the façade depict Sebastian, famously martyred by multiple arrows – the wounds were understood to represent the sores that were the most common outward mark of the plague.

The church of San Sebastiano is celebrated for its interior, where a series of paintings – mostly on canvas, some fresco – were produced by Paolo Veronese over a period of fifteen years from 1555, on the request of the prior of the church and monastery, who, like the artist, was from Verona. Altarpieces, organ shutters, the choir gallery, sacristy ceiling and church walls are all decorated in the bright colours and shimmering fabrics favoured by the artist, with many scenes celebrating the life and martyrdom of the church’s namesake.

Fabrizio Nevola

Further reading

The Church of San Sebastiano: https://www.savevenice.org/project/church-of-san-sebastiano

Jane Stevens Crawshaw, Plague hospitals: public health for the city in early modern Venice, Ashgate Publishing (2012)

Ronnie Ferguson, Venetian Inscriptions: Vernacular Writing for Public Display in Medieval and Renaissance Venice, Modern Humanities Research Association, 2021