Antifascist voices

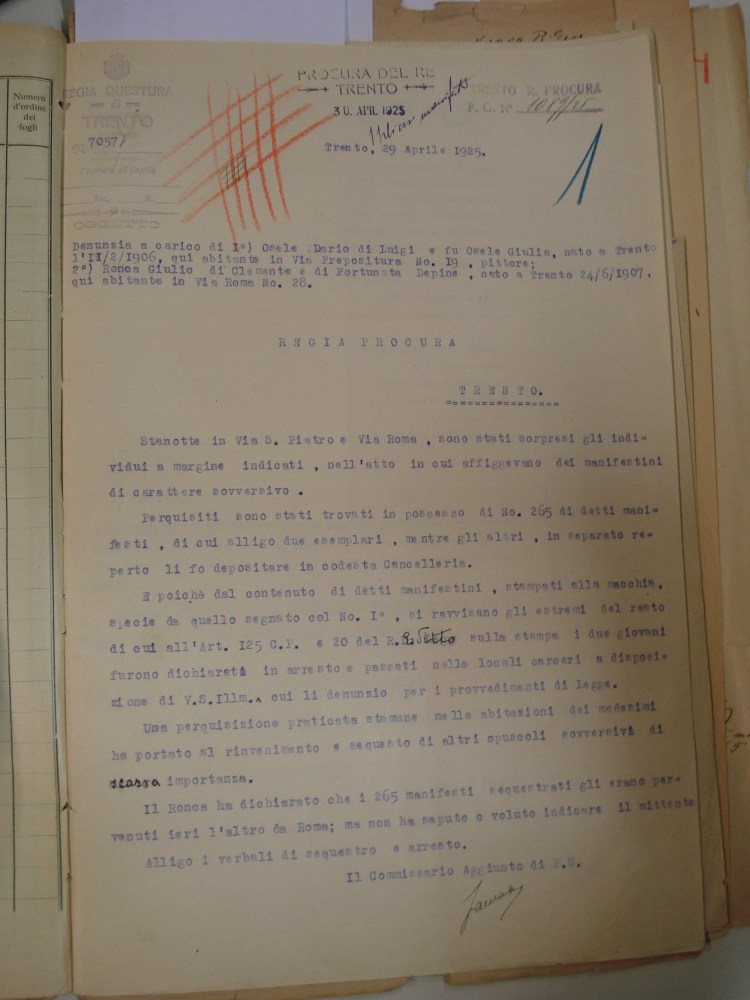

Analyzing police documents and trial files from the 1920s and 1930s, it emerges that opposition to fascism in Trentino, although less intense than in other Italian areas, was expressed in a wide variety of forms and practices. Examples include seditious cries shouted at night, insults and taunts against the Duce, protest songs sung in taverns, graffiti on walls and leaflets, but also the phenomenon of emigration, clandestine meetings and the dissemination of subversive and propaganda materials.

On the one hand, protest against the regime was expressed through thoughtful and articulated speeches and gestures, which denoted a greater degree of awareness on the part of the authors and a clearer political basis for their actions. On the other hand, dissent was made clear through episodes that may appear less politicized and more spontaneous. In this case, it was a question of behaviors that were often ambiguous, trapped in a “gray area” that was not always easy to decipher, halfway between delinquency, a certain rebelliousness, and open opposition. Ways of acting dictated by anger, by a state of drunkenness (often found in police sources), by difficult work situations, and by intense surveillance by public security agencies. The purely political nature of the forms that opposition to fascism took was also mixed with factors related to people’s daily lives.

Such manifestations of dissent may seem marginal compared to the more classic forms of organized protest or militancy in a political party. In the fascist society of the time, however, so rigidly hierarchical and militarized, the control exercised, not only by the State but also by the community itself, was so pervasive and all-encompassing that it nullified the most basic democratic principles. Freedom of speech was denied, political parties were dissolved, public discussions were harshly opposed and personal opinions were shaped and imposed from above. Schools, after-work organizations, various other associations and mass propaganda enveloped the individual in a tentacular way and were the tools to anesthetize the entire community. In this context, even the smallest gestures of rebellion take on a significance that deserves to be underlined.

Trentino, moreover, constitutes a border area where divisions, at the level of national and cultural belonging, between “Italians” and “Austrians” ran through society throughout the twenty-year fascist period. These tensions, which were not resolved with the transition from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the Kingdom of Italy following the First World War, joined other factors influencing opposition to fascism. In fact, among the police files there are arrests for having praised Austria or for having vilified the Italian flag. Compared to other areas of Italy, opposition to the regime in Trentino was thus enriched by issues of regional and national identity.

Michele Toss

Further reading:

Fabrizio Rasera, Fascisti e antifascisti. Appunti per molte storie da scrivere, in Mario Allegri (edd.), Rovereto in Italia dall’irredentismo agli anni del fascismo (1890-1939), Rovereto, Accademia roveretana degli Agiati, 2002, pp. 85-130

Vincenzo Calì, Paola Bernardi (edd.), Testimonianze. Trentino e trentini nell’antifascismo e nella Resistenza, Trento, Temi, 2016