Foreign writers and the antifascist cause

For more than a generation after the end of the Spanish Civil War, discussion of foreign experiences in the Republican zone tended to revolve around the words of intellectuals rather than the actions of a far greater number of working-class volunteers who fought in the International Brigades. This is due to the obvious fact that highly educated, erudite and well-known writers – many of whom gravitated to the Hotel Metropol in Valencia – could more easily make their voices heard.

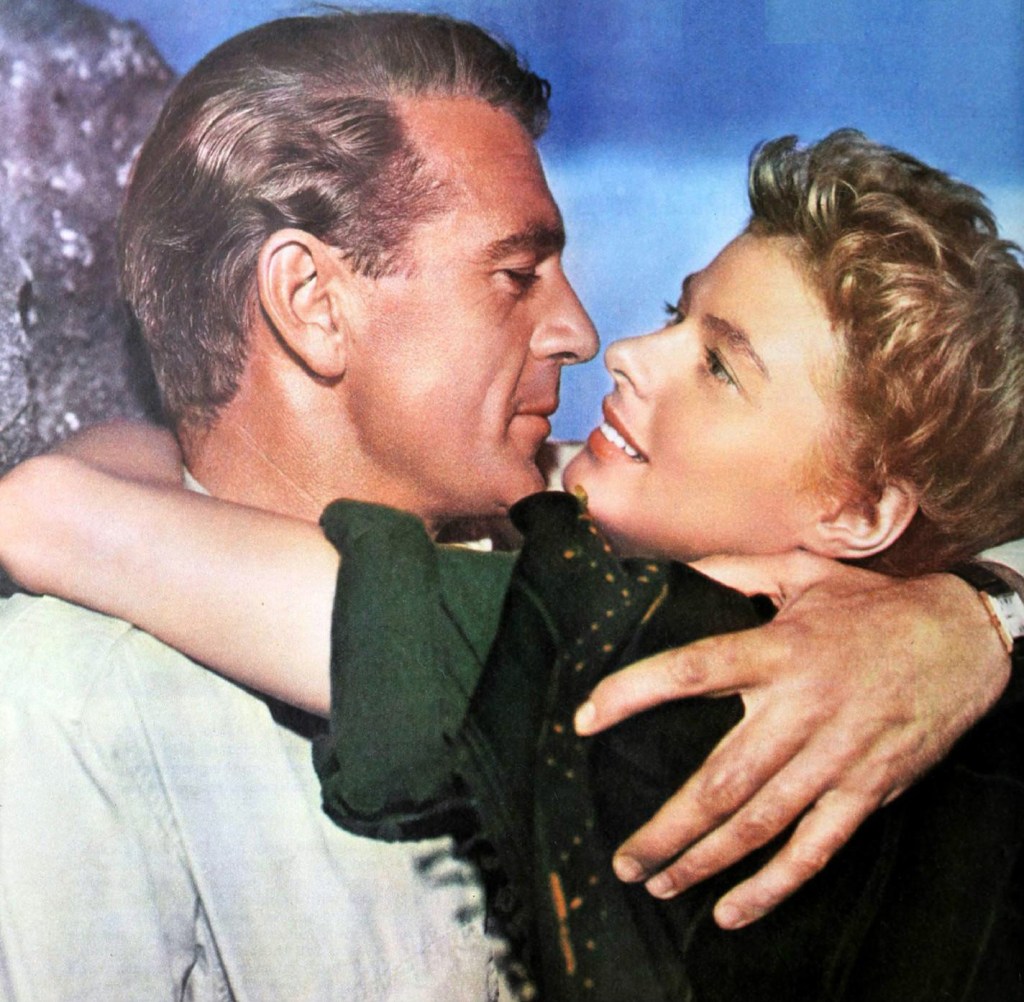

Ernest Hemingway is a good example. Going to Spain in March 1937 as a correspondent for the North American Newspaper Alliance, his despatches were read by millions of American readers, and For Whom the Bell Tolls is perhaps the most famous novel to have been written about the conflict. Its hero, Robert Jordan, is a projection of how many liberal intellectuals saw the war. A teacher turned guerrilla, Jordan did not go to fight in another country for a political party but for humanity itself; to save the Republic was to save the world. Indeed, the fact that the Republic lost only sanctified the antifascist struggle. The defeated Republic, never having to face grubby postwar realities, became the ‘last great cause’.

Nonetheless, while the war lasted, the Republican government was not blind to the propaganda opportunities offered by the support of famous foreign intellectuals, particularly those in Western democracies critical of their own governments’ policy of non-intervention. The Second International Congress for the Defence of Culture (to give its official title), may have been inaugurated at City Hall in Valencia on 4 July 1937, but it also held sessions in Madrid and Barcelona before closing in Paris a fortnight later.

One should not suppose that foreign intellectuals who participated in the congress had a better understanding of Spain than those antifascist volunteers who did not pen for a living. The British poet W.H. Auden, in his rousing 1937 composition Spain, described the country as ‘a dry square, snipped from Africa and welded to Europe’. Progressive writers did not simply regurgitate ‘black legend’ tropes about Spaniards. Many also chose to close their eyes to the more disagreeable aspects of Republican Spain. Henry Kamen reminds us that in 1936, liberal intellectuals were in as much danger from revolutionary ‘checas’ than fascist death squads, yet rebel brutality featured more prominently in their writings. Indeed, Hemingway would write his only play on the Fifth Column in 1938, which repeated Republican claims about its essentially terrorist nature.

Yet this is perhaps beside the point. Intellectual engagement with Spain was not about reflection but action. In 1937, the poet and activist Nancy Cunard asked fellow writers in Britain what side they were on. The responses, published as Authors Take Sides, revealed that ‘For the Republic, against Franco and Fascism: 127. Neutral: 16. Pro-Franco and Pro-Fascism: 5’. George Orwell, having escaped arrest in Barcelona, refused to take part, asking Cunard to ‘stop sending me this bloody rubbish’. Orwell found that to challenge the dominant antifascist narrative was to invite ostracism. His Homage to Catalonia, a searing indictment of communism in Republican Spain, was rejected by his usual publisher Victor Gollancz and largely ignored before the author’s death in 1950. The Cold War would transform his reputation. Many writers who had once celebrated the role of communism in the civil war now embraced Orwell as a prophet. In the year of his death, the disillusioned poet Stephen Spender, a participant in the July 1937 writers’ congress, contributed to a collection of essays denouncing the evils of Stalinism. It title was ‘The God That Failed’.

Julius Ruiz

Further reading

- Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls (Scribner, 2020)

- Henry Kamen, The Disinherited: Exile and the Making of Spanish Culture, 1492-1975 (HarperCollins, 2007)

- Richard Crossman, The God That Failed (Columbia University Press, 2001)