Shaping the regime’s citizens

From the early 1920s, education and instruction became the cardinal elements in the creation of the new fascist citizen.

Both during childhood and adolescence, the schools and organizations of the regime marked the time and space of youth by applying the dictates of Mussolini’s doctrine: order, discipline and hierarchy. From 8 to 14 years, a child became a Balilla if a boy or a Piccola italiana, a Little Italian, if a girl; from 14 to 18 years old, an Avant-gardist and a Young Italian girl; finally Italian youth joined university groups and the party.

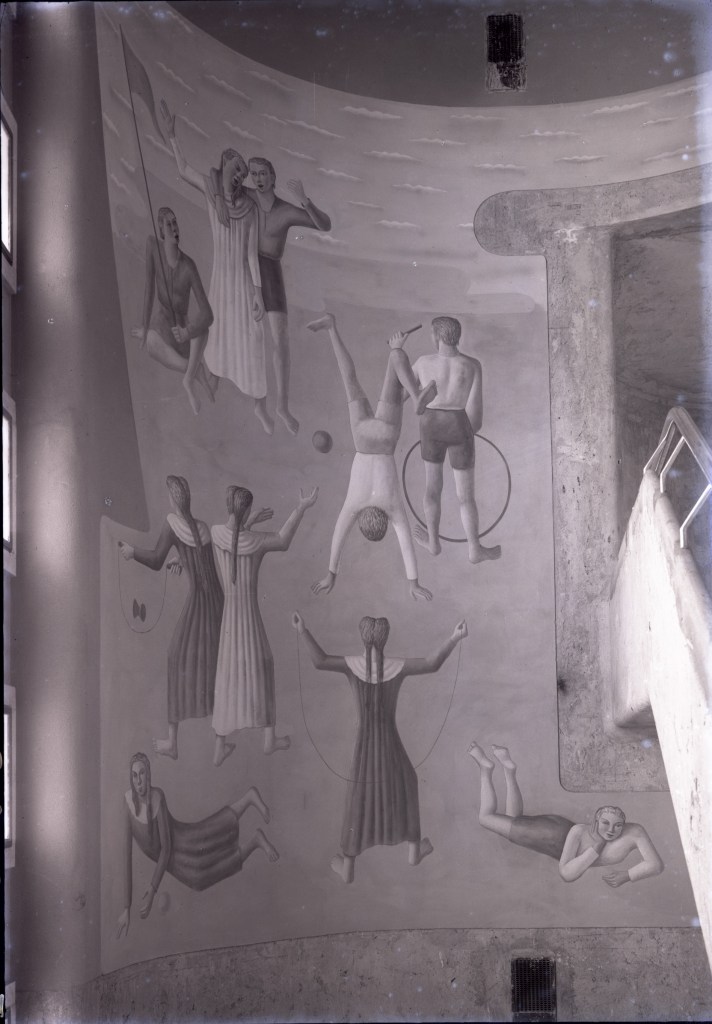

Inside and outside of schools, fascism organised girls and boys in paramilitary forms, promoting the cult of the leader and the care of physical strength, arranging collective rallies, treating education as a tool of propaganda. In the classrooms, the image of the Duce stood out alongside the king and the crucifix while the history of the regime is narrated in the textbooks. The Roman salute was introduced as were the celebrations of the March on Rome, the Great War and, in the second half of the 1930s, the Fascist Empire. The self was overwhelmed by a public ideal, by an increasingly close relationship between school, society and politics that extended well beyond teaching activities, generating, even in Trentino, open conflicts with Catholic institutions and practices.

The interest in the educational field materialised in an unparalleled legislative fervour that began with the Gentile reform of 1923 and ended with the School Charter signed by Bottai in 1939. Gentile’s directives promoted the elitist nature of secondary education by rejecting the idea of a mass school, suppressing school councils, and raising the position of the superintendent. The basic school, called elementary, was also reformed, divided between state schools, temporary schools to be entrusted to institutions such as the Opera Nazionale di Assistenza all’Italia Redenta and subsidized schools managed by private individuals. After the Concordat with the Papacy of 1929, the role of the Catholic religion was central, positioned as the “foundation” of the educational system.

Schooling was compulsory from 6 to 14 years, a novelty for the Italian context but not for Trentino. In the region, the over 2,000 teachers – mostly women – were the backbone of a small army, in urban areas and in isolated mountain centers. The rise of “action groups”, libraries, educational exhibitions and school newspapers were designed to spread fascist propaganda that was unconcerned about its contradictions, of an educational policy based more on regimentation than on pedagogy, intent on training not men and women, but fascists.

Giorgio Lucaroni

Further reading:

Jürgen Charnitzky, Fascismo e scuola. La politica scolastica del regime 1922-1943, La Nuova Italia, Firenze, 1996

Quinto Antonelli, Storia della scuola trentina. Dall’umanesimo al fascismo, il Margine, Trento 2013