Carceral archipelago

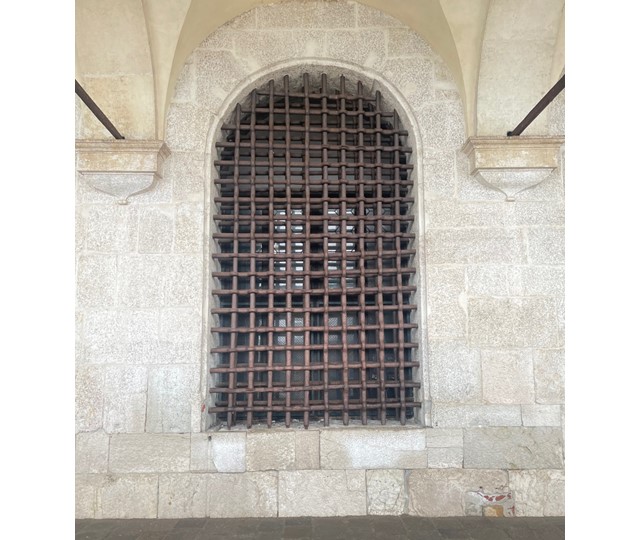

Venice’s early modern criminal justice system was an outlier as compared to the rest of Europe. Most of Europe saw a shift from corporal punishment to imprisonment as the dominant sentence for criminals in the eighteenth century, with a rapid increase in prison sentences in the last quarter of the century. But Venice had used incarceration for centuries by then. The building you see here was built between 1589-1614, and linked to the Palazzo Ducale by the so-called ‘Bridge of Sighs,’ the name some Romantic poets gave the passageway, imagining the prisoners taking one last look out the windows towards the lagoon.

Several courts used these prisons, including the Executors Against Blasphemy, the Inquisition, the Council of Ten, and the Lords of the Night. The building also included infirmaries, a chapel, separate cells for female prisoners, a courtroom, an archive, a torture chamber, a place to keep stolen goods, and spaces for the guards.

Sentences passed by the Executors against Blasphemy could range from as little as a month to as much as a decade. More severe sentences were to cells “all’oscuro,” or in the dark, lacking windows, while lighter sentences were “alla luce,” cells with windows that let in fresh air and natural light. The conditions a prisoner was kept in also varied based on the level of his or her cell; those at the bottom often flooded with high tide, while those at the top, under the lead roof (the infamous piombi, from which Casanova escaped), became unbearably hot in summer. Pleas for mercy from prisoners often included notes from medical professionals, testifying to the insalubrious conditions that led to long-term poor health.

Although these were the main prisons of Venice, there were other places where problematic people could be locked away. There are cells still visible in the ground floor of the Palazzo dei Camerlenghi, next to the Rialto Bridge, in which people who defaulted on their debts were held. There were also various other locations for those who somehow caused a disruption, even if they did not violate the law. Unruly women could end up in religious refuges, whether they wanted to or not; sufferers of syphilis could be confined to the Incurabili on the Zattere. Travelers coming from plague-infested ports were temporarily confined to the Lazzaretto Nuovo, while those infected were sent to the Lazzaretto Vecchio, from which they were unlikely to return. Both of these were islands, helping to contain potential or real infection. From 1716, the Venetian Senate designated yet another island, San Servolo, as a military hospital, but from 1725 it also was used to segregate the mentally ill from the rest of society. It remained a psychiatric facility until 1978.

Celeste McNamara

Further Reading:

Franzoi, Umberto. Le prigioni della Repubblica di Venezia. Venice: Venezia editrice, 1966.

Povolo, Claudio, and Giovanni Chiodi, eds. L’amministrazione della giustizia penale nella Repubblica di Venezia (secoli XVI-XVIII). I. Lorenzo Priori e la sua Prattica Criminale. II. Retoriche, stereotipi, prassi. Verona: Cierre edizioni, 2004.

Scarabello, Giovanni. Carcerati e carceri a Venezia nell’età moderna. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1979.

Shaw, James. The Justice of Venice: Authorities and Liberties in the Urban Economy, 1550-1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.