Ritual warfare

The Ponte dei Pugni is named for the fist fights that are known to have taken place here, described in the records as ‘Battagliole sui ponti’, or bridge skirmishes. As you’ll have gathered from references throughout the Hidden Venice app trail and these webpages, the battles were fought between two rival factions of popolani worker/artisans: the Castellani, mostly from the shipyards, and the Nicolotti many of them fishermen from the southern part of the city. The significance of the bridges? These were positioned on the borders of areas that were controlled by these rival factions. The battle on a bridge was a fight for supremacy and control of these ephemeral borders, a violent yet ritualised expression of (toxic) masculinity of the city’s working male population. When such a battle was planned the build-up was over a number of days, as the factions prepared for the event, and large numbers of workers from the Arsenale – who made up the core of the Castellani faction – would make their way across the city to the bridge.

Technically, the fights were illegal, though at least in the seventeenth century they appear to have had support from elite patrons. The law only got involved if they really got out of hand, although bans on clubs and shields and records of fatalities are a reminder of how violent these battles could actually be. By around 1600 the fights were restricted solely to fists, and the most detailed accounts describing them are by an anonymous nobleman, perhaps one of those that had paid handsomely for tickets to get a good window-seat view. But élite interest in the spectacle declined through the eighteenth century and regulation ultimately led to the end of the practice.

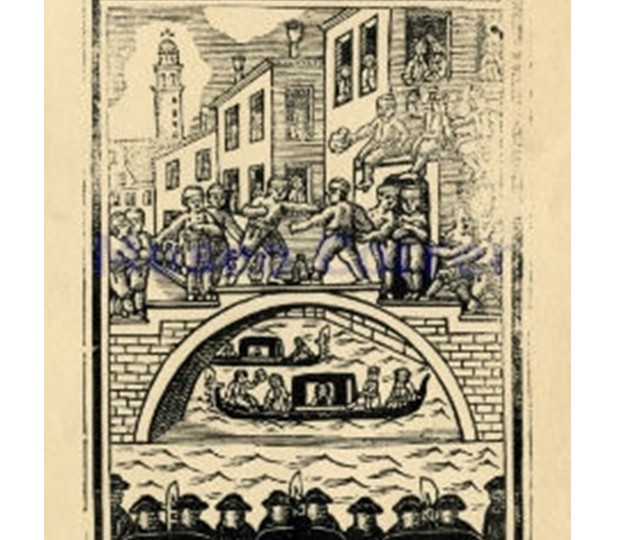

Many paintings and mass-produced prints are a testament to the popularity of the ‘battagliole’ as a spectator sport, and such was the spectacle that on a number of occasions they were scheduled to entertain visiting dignitaries. So, for example, in 1574 a bridge battle involving about 600 artisans was organised to mark the visit of King Henry III of France, who is reported to have commented that it “was too small to be a real war and too cruel to be a game.” Nevertheless, as the illustrations of the battles show, these events took place in front of large crowds of spectators that filled the windows and balconies surrounding the bridge, as well as from boats and barges moored up along the canal to provide the best vantage points.

Fabrizio Nevola

Further reading

Robert C. Davis, The War of the Fists, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Robert C. Davis, ‘The Police and the Pugni: Sport and Social Control in Early-Modern Venice’, Stanford Humanities Review 6.2 (1998)