Shipbuilding and warfare

Venice’s shipyards, the Arsenale, were founded around the early twelfth century and grew to become one of the largest proto-industrial complexes in the pre-modern world. The Arsenale was closely policed and surrounded by high walls to prevent spies from stealing Venice’s industrial secrets, although eminent visitors were given tours of this pride of the Republic. In the massive sheds inside, workers produced the ropes, rigging, munitions and different parts of the ships in a kind of assembly line, so that a huge vessel could be put together at astonishing speed. The size and efficiency of this complex in the production of both war and merchant ships for the enormous Venetian fleet was essential to Venice’s maritime and commercial power.

The historian Robert Davis likens the Arsenale to a “company town”, with hundreds of men and women going in to work there every day in the sixteenth century. (The workforce was doubled in this period because of the threat of war with the Ottomans). The arsenalotti received a secure salary and various perks, such as exemption from some taxes. Arsenal workers also were given significant quantities of (watered down) wine. In the seventeenth century, an actual fountain of wine was installed in the caneva or wine cellar of the Arsenale, which became an important space of sociability for workers and a symbol of the munificence of the state to its employees.

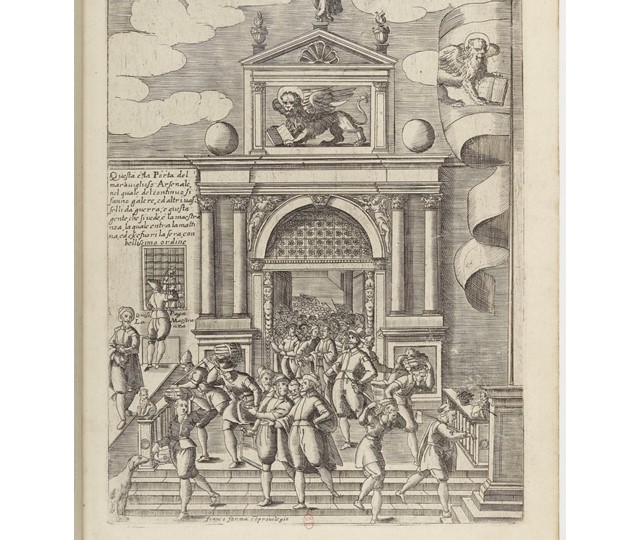

The Arsenale’s main gate was constructed around 1460 and modelled on a triumphal arch in the Istrian city of Pula, then part of the Venetian maritime empire. Two winged victories flanking the gate, as well as a commemorative inscription, were added after the Venetian victory over the Ottomans, as part of a Holy League of Christian states, at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. However, the sense of triumph was short-lived, as in the same year Venice lost the island of Cyprus, which it had dominated since 1489, to the Ottomans. The loss was a major blow to Venetian dominance in the Mediterranean, which would steadily decline from this point. It also provoked another flow of refugees towards Venice, and Cypriots became a larger component of Venice’s Greek community from this time. Yet more migrants would arrive half a century later, when Venice lost Crete to the Ottomans.

The Venetians did, however, reconquer the Morea or Peloponnese region in the late seventeenth century at which point the two lions beside the Arsenale gate were added, taken from Greece as spoils of war. Even as the Greek migrants who arrived in Venice during the Renaissance blended into the Venetian community over time, they left an important and enduring imprint on the culture and fabric of the city.

Rosa Salzberg

Further reading

Robert C. Davis. Shipbuilders of the Venetian Arsenal. Workers and Workplace in the Preindustrial City. Baltimore & London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

Robert C. Davis. “Venetian Shipbuilders and the Fountain of Wine”, Past & Present, 156 (1997): 55-87.

Ralph Lieberman. “Real Architecture, Imaginary History: The Arsenale Gate as Venetian Mythology”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 54 (1991): 117–26.