Cesare Battisti: the remaking of a martyr

Socialist, irredentist, scientist, martyr, Cesare Battisti is among the most famous figures in the history of Trentino. Having enlisted as a volunteer in the ranks of the Royal Army and hanged by the Austrians in July 1916, the lieutenant/geographer quickly became a symbol of resistance to the foreign yoke, occupying a central position in the pantheon of heroes produced by the Great War.

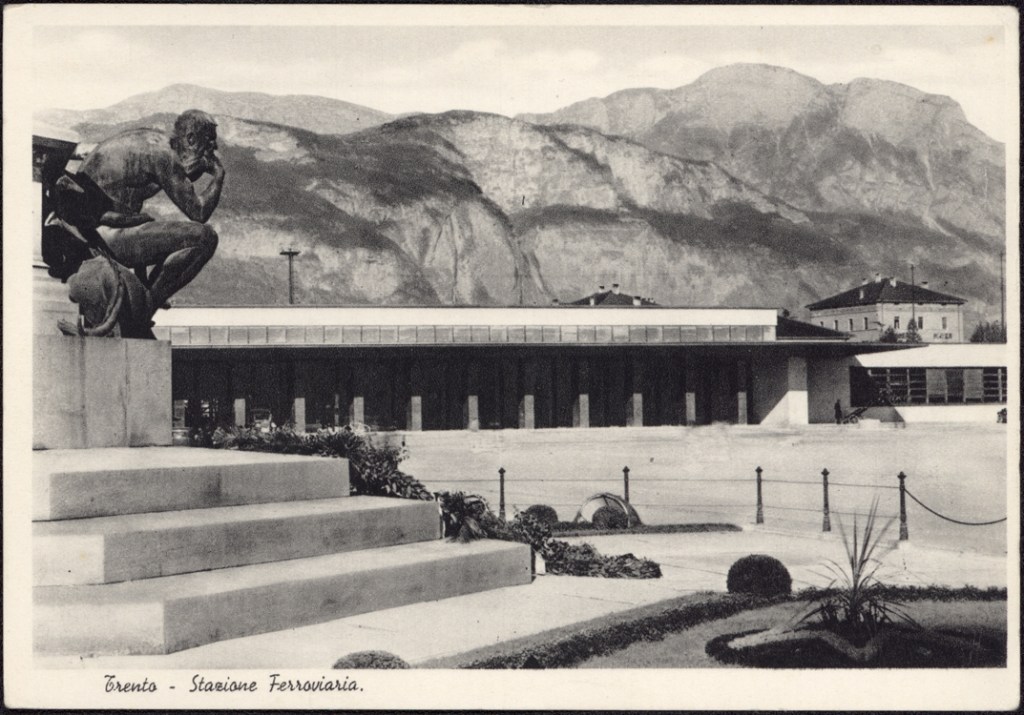

Although opposed by his widow Ernesta Bittanti, the first liberal and then fascist reinterpretation of Battisti’s sacrifice was articulated above all through architecture: from the Monument to Victory in Bolzano – initially to be dedicated to the martyr – designed by Marcello Piacentini and inaugurated in 1928, to the mausoleum erected on the Doss which, still today, houses the remains of the Trentino patriot.

Planned since 1916, abandoned and taken up again between 1922 and 1926, and finally built between 1932 and 1935, the Doss mausoleum – a circular monument with columns by Ettore Fagiuoli – dominates the valley from the hill that for 68 years had hosted Austrian fortifications, symbolically returning it to the city. Inside the tomb, an invocation by Giuseppe Gerola, selected by Mussolini from the proposals received from various Trentino intellectuals, reads: «To Cesare Battisti who prepared Trento for the union with the homeland and a new destiny», an exaltation of an irredentism that no longer finds its raison d’être in nationalism but in the future of the fascist homeland.

The inauguration on May 26, 1935, expressed this celebratory and spiritual claim. The family is granted the honor of transporting the body and a wake, though a private translation of Battisti to his final resting place was denied. Luigi Razza, Minister of Public Works, arrives on behalf of the government, while the Duce orders that the wreath of the Trentino prefecture bear the words “the Fascist Government” and not “the Head of Government”.

Yet, in the face of Mussolini’s reserve, the chronicles tell of a ceremony with great emotional impact. Flagpoles, garlands and tapestries crowd along the route of the procession – from the cemetery to the Doss – dotted with 156 wreaths. At the exit of the cemetery, an eight-meter-high drapery with the word “present”, illuminated at night, stood out, while in Via Belenzani, 34 Roman columns over 3 meters high were placed, surmounted by golden eagles, as well as two fasces at the entrance to the San Lorenzo bridge. On the hill, at the moment of burial, in the presence of the king, all the bell towers of Italy resound for five minutes – not for the ten proposed – to sanction a ceremony perhaps more mournful than solemn, a sacralization that, however imperfect, elevates the Italian martyr to a fascist martyr.

Giorgio Lucaroni

Further reading:

Bruno Tobia, Dal milite ignoto al nazionalismo monumentale fascista (1921-1940), in Walter Barberis (ed.), Storia d’Italia: Annali 18. Guerra e pace, Einaudi, Torino, 2002, pp. 605-642

Massimo Tiezzi, L’eroe conteso. La costruzione del mito di Cesare Battisti negli anni 1916-1935, Museo Storico in Trento, Trento, 2007